In the lingering aftermath of the True Bloods, Dracula Untold and Twilights of modern vintage, we’re quietly in the midst of a vampire revival – between Netflix’s underrated Castlevania series and modern interpretations like Penny Dreadful and Midnight Mass (or even, to a degree, What We Do in the Shadows), the “horny, undead bloodsucker” genre is in a much more interesting place than it’s been for the past few decades – which made it all the more exciting when it was announced in 2017 that Rogert Eggers (the director/writer behind The Witch, The Northman, and The Lighthouse) would take on the challenge of updating 1922’s Nosferatu and Warner Herzog’s 1976’s Nosferatu the Vampyre with his own take on Count Orlok (the “unofficial” Dracula) and his tale of romantic obsession and woe.

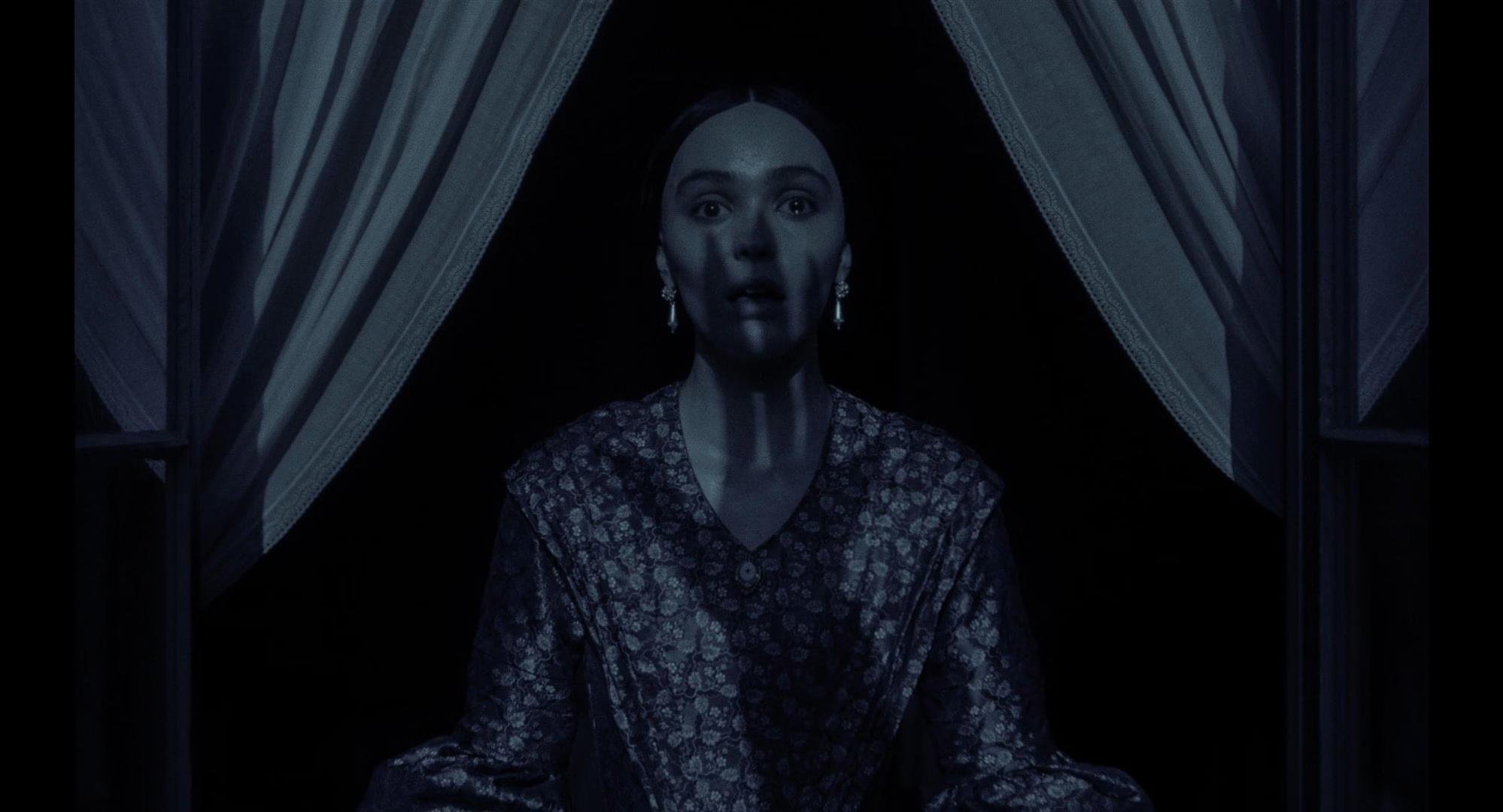

And boy, does he deliver: Eggers’s Nosferatu is a grotesque gothic delight – especially once the film works through a stiff opening act, and begins to embrace some of the weirder, more unsettling elements lying in its subtext. Unsettlingly horny and atmospheric, Nosferatu is at once familiar and curious, especially as the film leans further and further into the lead performances of Lily Rose-Depp as newly-married, eternally melancholic Ellen, and Bill Skarsgård, whose voice-contorting, prosthetic-laden performance as Orlok stands as one of his most fully-realized performances (which helps it feel like a typecast performance, given his already iconic work in films like IT).

Nosferatu does begin a bit slowly, a byproduct of initially centering its story around Nicholaus Hoult’s Thomas, as he takes on a doomed real estate job to produce income while his wife Ellen recovers from a strange, inexplicable case of post-nuptial melancholy. As the film begins, Egger’s inclination to explore the seduction of the supernatural in pursuit of clarity feels almost muted from what the trailers would purport; through Hoult’s restrained performance, Nosferatu initially feels a bit of a stiff period film – though once his character leaves home near the end of the first act, what were monochronistic allusions to the unsettling slowly begin to build and form the unsettling visual language and structure of the film, which float from scene to scene until Thomas makes his way into Orlok’s ominous estate, where the titular character of the film is introduced, and begins to unspindle the film’s carefully constructed reality.

From there, Nosferatu blossoms as familiar themes of Egger’s films and past interpretations begin to find their way to the surface; Thomas’s persistence, Ellen’s long-gestating dread, and Orlok’s tempestuous infatuation begin to percolate in the film’s central third, which focuses mostly on Ellen’s slowly-degrading mental state and the introduction of occult philosopher Albin Eberhart Von Franz (Willam Dafoe, vibrating on his own frequency in most scenes). It’s here where the film’s many different elements begin to percolate, and the film’s louder performances begin to align with the film’s incredibly moody score (provided by Robin Carolan, who made his debut on The Northman) – setting the stage for the film’s operatic third act, where Nosferatu becomes richly concupiscent amidst the backdrop of the plague landing in Ellen’s town.

It takes a bit too long to get there, with a few too many scenes from an unsurprisingly stiff Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Emma Corrin as a couple who get caught up in Ellen’s destiny – but when it does, Nosferatu explodes into a violent cacophony of discordant strings, unsettling desires, and dreadful inevitably, slowly allowing its titular character further and further into the center of the frame, as he makes his way to Wisburg for the film’s inevitable, magnanimous climax. And what a climax it is; Nosferatu’s final minutes are ascendant, delivering on its promise of a gothic fever pitch film by stepping fully into its own identity, establishing itself alongside the classic vampire films it welcomely leans into the shadows of in the process.

It’s a fantastic final set of scenes, drenched in the visual and emotional aesthetics of Victorian horror (the film’s costuming is absolutely immaculate, which helps with this) – its a gambit by Eggers, who builds methodically to those final moments, so much so that it leaves some of its characters feeling a bit flat at the end, even Orlok, whose tragic arc remains shapeless in a way that allows it to be reverent and considering of its source material, but a bit hollow as a companion piece to Ellen’s tale of loneliness and purpose, and the film’s exploration of the unsettling power found where fear and seduction meet. Nevertheless, its final images conjure up a powerful emotional response, its poignantly disturbing images of plague, regret, death, and fulfilled desire an intoxicating mix of aesthetics and emotion, the kind only the great filmmakers can consistently tap into.

Though Nosferatu is bookended with its most evocative images and powerful moments, how Eggers plays with expectations throughout is incredibly engaging, as it rapidly shifts tones and emotions to create an inexplicable sense of anticipatory dread. And most importantly, when the film shifts to deliver on that promise, it crescendos in elegantly unsettling fashion, embracing a combination of practical and visual effects that bridges the gap between Eggers’ vision and his film’s inspiratory works (not to mention Nosferatu’s incredibly stripped down, focused color grading, one of the better lit “dark” films of recent vintage). Though hardly the most notable holiday movie this year about an iconic outcast, Nosferatu, in all its baroque, grotesque glory, might just be the best of them, a beautifully imperfect examination of the timeless, consuming pursuits of desire, love, and fate – wrapped in a wonderfully blood-soaked, monochromatic package all of its own.

Grade: B+

Discover more from Processed Media

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.